Are you an aspiring aviator or a professional pilot seeking your first turbine pilot job? In this blog post, we will guide you through the path from challenges to rewards, helping you navigate your way to success in the world of turbine pilot jobs. This article explores the challenges, rewards, and opportunities of advancing into your first turbine pilot job. If you’re ready to embark on your journey towards your first turbine pilot job, let’s dive in and discover the possibilities.

Transitioning from entry-level pilot positions in piston aircraft to more advanced roles in turbine aircraft is an essential progression that many pilots undertake to further their careers. While this leap may present challenges, it is an attainable milestone for most pilots aiming to advance their career.

What is a Turbine Airplane

There is a misconception among the public that airplanes are divided between prop and jet. They make the assumption that any propellor they see means the engine powering it is similar to the engine in their car.

Turbine engines have broad uses beyond the public perception. Variations of turbine engines include:

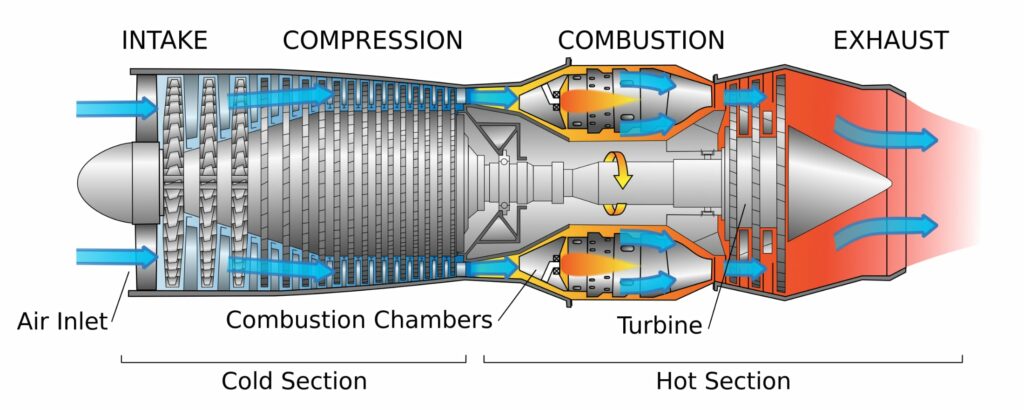

- Turbojet: the base turbine engine core. These are more pure jets and produce power from just the engine core. These are the original turbine engines and aren’t as common now as they are inefficient and loud.

- Turbofan: this powerplant takes the original turbine engine core and puts a large shrouded fan in front. A significant amount of thrust generated by the engine comes from the fan rather than the core. This is the common ‘jet’ engine in use today.

- Turboprop: the turbine core delivers power to a gear box which spins a propellor.

- Turboshaft: similar to a turboprop in that the engine core supplies power to a gear box. Turboshafts differ in that they drive a gear box or transmission that is not structurally attached to the engine itself.

The two main types of turbine engines in civilian use are turboprops and turbofans. Turboprop-powered airplanes are generally slower and don’t fly as high as turbofan-powered airplanes but are often just as advanced. Turboprop airplanes have similar system redundancy and ability to contend with difficult operating environments.

Geared Turbofan – A New Class

In recent years a hybrid engine has entered airline service. The geared turbofan powers a large ducted fan using a gearbox similar to turboprops. The geared turbofan has improved efficiency and makes less noise versus non-geared turbofan engines. It is built by Pratt & Whitney and is in use on the Airbus A220, E2 variants of the Embraer E-Jets family, and is an optional engine on the NEO variants of the Airbus A319, A320, and A321.

The Challenges of Flying a Turbine Airplane

The step into turbine airplanes can be a challenging advancement for pilots making the switch for the first time. Complicated systems, faster speeds, and more challenging environments make for a steep learning curve. But most pilot employers have proven training plans to help pilots with this transition.

Complicated Systems

Turbine-powered airplanes have a large amount of complicated systems. Some of these systems are related to the airplane being bigger, others are related to passenger and crew comfort, while other systems are related to operating in foul weather. The more complicated systems include:

- Pneumatic: this includes bleed air systems where air is drawn from engines to power other systems. Downstream consumers of bleed air include cabin environmental and pressurization systems, anti-ice and de-ice systems, and in some cases charging accumulators associated with hydraulic, fuel, or water systems.

- Anti-Ice, Rain: flight deck window heat, windshield wipers, probe heat, and anti-ice/de-ice systems that either prevent ice from accumulating on lift generating surfaces and engines, or break the ice off after it’s accumulated.

- Automatic Flight: flight director, autopilot, autothrottle/autothrust

- Communications: VHF communication, HF communication, SELCAL, SATCOM, CPDLC, and internal communication systems.

- Electrical: generators/alternators, backup systems, power distribution systems and logic

- Engine, APU: main turbine engines and the auxiliary power unit (APU)

- Fire Protection: engine/APU fire protection, cargo fire protection, and cabin fire protection systems.

- Flight Controls: often hydraulically moved, and with many modern airplanes are fly-by-wire. Air Transport airplanes have large multi-segmented flap and slat systems on the wings.

- Flight Instruments, Displays: most are advanced EFIS display systems

- Flight Management, Navigation: includes Flight Management Systems. Many modern turbine-powered airplanes are operated and managed through Flight Management Systems. Navigation systems are much more complex and capable.

- Fuel: storage and distribution systems. Many turbine-powered airplanes carry considerable amounts of fuel and need complex fuel systems to manage the fuel throughout the flight.

- Hydraulics: power consumers such as flight controls, landing gear retraction/extension, nose wheel steering, and brakes. There’s significant redundancy in hydraulic systems, and the consumers of hydraulic systems usually have additional redundancy.

- Landing Gear: most are retractable. Multi-disc or anti-skid braking systems. Landing gear on turbine planes need to support a lot of force.

- Warning Systems: pilots need to be aware of how their airplane type alerts them. There are different levels of warning systems, as well as logic behind the warning system inhibition during certain phases of flight.

There is a wide range of how directly involved pilots must be in the daily operations of systems. On some airplanes computer automation will manage a large portion of the system control. On other airplane types some or most of the systems will have to be manually controlled by the pilot(s). Either way, pilots must have solid knowledge of the systems operations, to be able to better work with their airplane and maintain situational awareness of what their airplane is doing and also in case of system abnormalities and emergencies.

Where a pilot might fly multiple variations of the same airplane type, such as different variants of the 737, training programs will teach a base variant and will have a separate module for differences on other variants.

Faster Speeds

Turbine-powered airplanes operate at much higher speeds, higher altitudes, and have a great deal more energy that needs to be managed. Descent planning can be complicated and needs to be done more than 100 miles from the destination.

Challenging Environments

A large part of the challenge of flying turbine airplanes is not in the airplane itself but in the environment in which they operate. When flying piston engine airplanes pilots are often flying in a training or hobby environment where good weather and light traffic prevail.

Turbine airplanes are more capable of flying safely through what would be hazardous weather for piston airplanes. Turbine-powered airplanes continue to work, regardless of the weather. Turbine pilots will experience more icing, more instrument conditions, instrument approaches flown closer to minimum decision altitudes and in low visibility, more turbulence, and will have to frequently avoid convective weather while flying.

Turbine airplanes operate at complex airports with heavy traffic, they fly multi-segmented departure and arrival procedures that include altitude and airspeed restrictions. Pilots need to be very proficient with air traffic control procedures and in radio communication. They need to be vigilant for other traffic as they are frequently in busy airspace. The large airports that turbine-powered airplanes fly into and out of can have complicated layouts, with air traffic controllers that bark out taxi instructions in fast staccatos.

Applying an Airplane to a Mission

When a pilot first starts in their aviation career they operate in the general aviation environment. The goal is to first learn how to fly and then gain experience. This environment is often self-paced, with few outside stressors causing a pilot to feel hurried.

When pilots advance into their first turbine position they are then flying airplanes that are being applied to a specific mission. A mission that has external pressures and additional duties not directly related to flying the airplane. Newer pilots underestimate the amount of additional challenge that comes with flying airplanes that are applied to specific missions. But then most pilots adapt quickly to this aspect of the pilot career.

Employer Training is Paced Faster Than Primary Training

New pilot training is a significant cost for employers. Because of this, the training programs are compressed compared to what pilots typically experience when they are initially pursuing their licenses. In particular, new hire airline pilot training is equated to trying to get a drink of water from a fire hose.

Turbine airplane training will usually include many phases:

- Initial indoctrination: covers working at that employer as well as operating procedures and specifications

- Emergency equipment training

- Airplane systems training

- Training programs are increasingly including a larger footprint of procedures training. Which entails time in what are known as flat panel trainers. This training focuses on bridging the knowledge of systems into operational procedures.

- Simulator training

- Initial operating experience (IOE or OE) which is learning to fly the airplane in service

While employer training can seem daunting, know that employers have a stake in your success. It is fast-paced, but employers still want to see pilots succeed. And the employers purposefully gear their training programs to walk the fine line between trainee success and compressing the footprint to save money.

Reasons for Flying a Turbine Airplane

While it may seem daunting the reasons for advancing into a turbine pilot job are numerous and well worth the extra training and responsibility.

Career Advancement

Pilot career progression options can vary. However, most pilots follow pretty specific paths with the goal of working for a major or legacy airline, a large cargo operator, or in corporate aviation. Each of these paths requires a step up into turbine-powered airplanes as pilots advance from their first pilot jobs into a mid career position. The pilot jobs seen as end goals by most pilots usually require minimum turbine engine experience before a pilot candidate is seen as competitive for the position.

Increased Compensation

With the typical pilot career progression, as pilots advance in their career, compensation increases as airplanes get larger and more complicated. This is a reflection of the increased complexity of the airplanes and environment, the increased responsibility, and that pilot unions have been able to loosely tie the revenue an airplane can generate to the pay rates associated with it.

Improved Quality of Life

As pilots advance in their career into larger and more complicated airplanes their work schedules can improve. When airplane range increases and average flight segments get longer pilots can get more of their required work done in fewer days, leading to more days at home.

Many turbine pilot jobs fall under collective bargaining agreements associated with pilot unions. These agreements have significant protections around pilot’s working conditions, conditions of how pay is earned, and how pilots can be treated and used while on the clock.

Improved Safety

Turbine-powered airplanes are more capable at dealing with poor weather. Turbine engines themselves are more reliable and most airplanes powered by them have redundant powerplants that capable of keeping the airplane in the air should an engine fail. And turbine-powered airplanes have significant redundancy built into other systems as well.

In addition to the planes themselves, most turbine-powered airplanes are operated in highly structured and regulated ways. That is, the operation itself is safer through improved training, more restrictive and well-defined limitations on types of operations and safety margins, and more operational support. And operating in the two pilot crew found is in most turbine aircraft increasing safety.

How to Get a Turbine Pilot Job

Turbine pilot jobs are not typically available in entry-level positions. They are treated as a mid career step up position after a pilot has accumulated professional experience.

First turbine pilot jobs can include:

- Part 91 corporate operations or charter jobs. These are more general aviation oriented rather than large scale fractional operators. Turboprop operations are not uncommon in these types of operations.

- Many skydiving operations use turbine powered airplanes such as Cessna Caravans and Twin Otters.

- Some part 135 cargo operators use turbine powered airplanes. Pilots will need to have part 135 minimum time requirements to apply to these positions unless an employer has an approved second in command program.

- Some aerial EMT operators will hire pilots to fly turboprop air ambulance flights with lower experience. These operators typically require part 135 minimums.

- A few part 135 operators now have FAA approved second in command programs. This allows the operators to hire pilots at lower flight times than what is usually required. The pilots then fly as a first officer in an airplane that normally only requires one pilot, but they can log the flight time towards upgrading into a captain role with that employer.

Tips for Getting Your First Turbine Pilot Job

Getting your foot in the door for your first turbine pilot job entails much of the same strategy as for other pilot jobs:

- Focus on gaining quality flight experience. Employers will see some flight time as more valuable than others, such as multi-engine experience, actual instrument flight time, and working as a flight instructor.

- Formal education such as an associates degree or bachelors degree can help. In the current pilot hiring environment these degrees are generally not but can set you apart versus competitors.

- Network! As with any profession, networking is key. Reach out to target employers and begin conversations with them early. Let them know you are interested in working for them and that you are interested in how to make yourself more competitive for the position. And keep in regular contact with them as you gain experience.

- Always present yourself professionally. In any interaction with a potential employer have a professional appearance and act and speak professionally in any interaction.

There are numerous sources available for finding turbine pilot jobs. The most effective approach to beginning your search is to first determine your priorities, values, and goals. There are many paths pilots can take to get to their goals, so it would then be a good practice to figure out which path gets you to your goals efficiently while aligning closest with your life priorities. After that, you can then begin researching companies in that segment of the aviation market and narrow down your choices.

Greg started his professional pilot journey in 2002 after graduating from Embry Riddle. Since that time he has accumulated over 8,000 hours working as a pilot. Greg’s professional experience includes flight instructing, animal tracking, backcountry flying, forest firefighting, passenger charter, part 135 cargo, flying for a regional airline, a national low cost airline, a legacy airline, and also working as a manager in charge of Part 135 and Part 121 training programs.